New research from the Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group (TARG) at the University of Bristol’s School of Psychological Science has been described as “really interesting” by harm reduction expert Dr Sarah Jackson. The team used an approach called Mendelian randomisation to discover the actual facts about the level of risk posed by regular use of nicotine – and the answer is very positive.

If Dr Sarah Jackson says that the findings of a research project are “really interesting” then it is a given that they are. Dr Jackson is the Principal Research Fellow at the University College London’s Alcohol and Tobacco Research Group and has specialised in evaluating the effectiveness of smoking cessation approaches, including the evaluation of the real-world effectiveness of all the major quitting aids. This has included analysis of effects of vaping, a subject she has frequently spoken to her peers about at conferences. In addition, she sits on Action on Smoking and Health’s advisory council, the board of the London Smoking Cessation Transformation Programme, and is an editor for the research journal Addiction.

The team from Bristol’s Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group published “Estimating the health impact of nicotine exposure by dissecting the effects of nicotine versus non-nicotine constituents of tobacco smoke: A multivariable Mendelian randomisation study” this month. The research project included work by Marcus Munafò, again a highly respected academic in the world of vaping and tobacco harm reduction investigative projects.

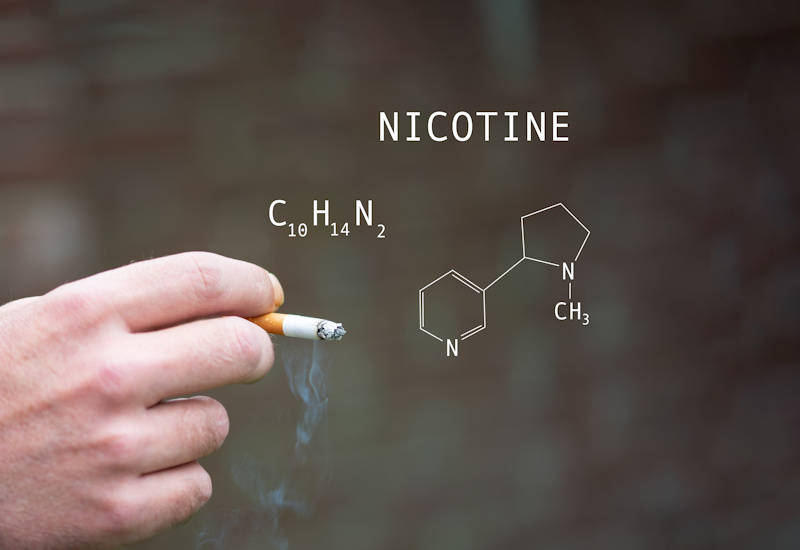

They say that the impact of smoking is well known but it is far less clear what the impact is of regularly using nicotine when it is not combined with the other products of burnt tobacco. As millions of people are now vaping on a daily basis, and using those devices across many years, they felt it has become “increasingly important to understand and separate the effects of nicotine use from the impact of tobacco smoke exposure”.

But they point out, “it is hard to disentangle the effects of regular nicotine use from the effects of tobacco smoke exposure”.

Professor Michael Russell is credited as being the father of the concept of tobacco harm reduction – a figure of such importance that he now has an award posthumously named after him. In 1976, he wrote: “People smoke for nicotine but they die from the tar”, and went on to advocate that the tar to nicotine relationship could play a fundamental role in making cigarettes safer – in particular, the development of low tar cigarettes.

With the advent of electronic cigarette devices in the early 2000s, he stated: “There is no good reason why a switch from tobacco products to less harmful nicotine delivery systems should not be encouraged.”

It is this thinking that lies behind the team from Bristol’s research: could it be shown that nicotine does not pose a health risk?

Dr Jasmine Khouja was the corresponding author for the research project, she explained their work: “There is a lot of research on how nicotine affects health. The effects are mostly short-lived, like increasing heart rate and blood pressure, and quickly return to normal.

Clinical trials using nicotine patches have also shown it’s safe when used for a short time, but we know less about what nicotine does to health when it’s used regularly for longer periods.

“Most of what we have learned has come from animal studies and from studies of people who smoke. This is problematic because we don’t know if humans will react the same as animals, and we can’t easily tease apart the effects of nicotine from the effects of everything else in cigarettes in the studies of people who smoke.”

People who use patches, sprays or gum only tend to use them during the period while they are attempting to quit smoking, and they quickly stop using them when they think they have escaped from tobacco’s clutches.

It’s a different kettle of fish for vapers.

Vaping works because it mimics many of the actions of smoking and allows adults to use their device until their brain registers that a suitable level of nicotine has been delivered to the blood (known as self-titration). People can adjust how frequently they use their device by changing the nicotine content of the eliquid or how much vapour is taken into the lungs, i.e. higher nic concentration juices or direct to lung style vaping leads to fewer hits being taken.

Because of the similarity of smoking to vaping, the ease of substitution means that ex-smokers continue to use their ecig equipment for long after they would have stopped using patches, sprays or gum.

Dr Khouja says: “We’ve used genetics to try and tease apart the health effects of nicotine from the effects of everything else in cigarette smoke. We found that nicotine is not driving the adverse health conditions seen in people who smoke: poor lung function, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer and coronary heart disease. However, it does increase heart rate.”

To help people understand the Mendelian randomisation process the team used she points interested readers to a 2-minute primer on YouTube.

“Mendelian randomisation looks at how your genes are linked to both an exposure (e.g., nicotine use) and an outcome (e.g., cancer), to understand if there’s a causal connection and account for confounding. Confounding happens when factors other than the exposure (e.g., nicotine exposure) being studied influence the results. Confounding can make it difficult to identify the true cause and effect,” Dr Khouja continues.

“Our genes are inherited randomly from our parents and don’t change when we’re exposed to confounding factors. Using genetics as a substitute for exposure in MR, researchers assume that any differences in health outcomes are linked to the specific factor they are studying. Using an extension of MR, multivariable MR, we can look at two exposures that have shared genetic causes at the same time and account further for confounding. This allows us to see if they both have an effect, or if just one of them is really causing the outcome.”

Ultimately, what did they find?

The authors of the study concluded: “We found that nicotine does not appear to be an independent cause of poor lung function, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or coronary heart disease, but does increase heart rate. These results support previous evidence which suggests that nicotine on its own does not directly cause poor health outcomes.”

Excellent news for anyone who has a relation worrying about their use of safer nicotine products like vapes.